Lessons from Unanticipated M&A Deals: How to Find Unique, Qualified Targets

Some of the most valuable and blockbuster deals that happened over the last 18 months consisted of unexpected buyers making big strategic bets in seemingly surprising areas outside their core business and comfort zones.

Microsoft acquired LinkedIn for $26.2 billion in 2016; CVS Health announced a $69 billion deal to purchase Aetna; Amazon and Walmart have each signed $600 million ($1.2 billion total) in options to buy shares in Plug Power, a hydrogen fuel cell technology company for distribution centers.

In hindsight, it is clear why these deals make sense from the buyer’s perspective and we can understand the transaction rationale for all parties involved, even though these deals surprised the market when they were announced.

LinkedIn provides Microsoft with social access to 433 million members that fit the profile of Microsoft’s ideal type of customer, in addition to a treasure trove of user data and market opportunities for building a hard-to-replace technology platform for professional software.

Aetna allows CVS to provide a vertically-integrated healthcare experience that leverages CVS’s current pharmacy business, Minute Clinics, physical infrastructure, customer data and operational synergies in helping customers better interface with the insurance aspect of healthcare. Together, Aetna and CVS can provide a one-stop-shop (insurance, diagnostic, preventive care, and prescription fulfillment) for day-to-day healthcare needs, thus providing a differentiated service to customers. The two companies can accomplish this goal without requiring vast expansions of either company’s infrastructure or radical changes in each company’s practices.

Amazon and Walmart are in many ways logistics companies that rely heavily on traditional forklifts and similar equipment powered by lead-acid batteries in their fulfillment and distribution centers. These antiquated batteries need to be swapped every few hours, charge in a separate and ventilated room, require special handling, and can cause massive operational bottlenecks that are increasingly unacceptable for 24/7/365 time-sensitive logistics operations.

The interesting question is not about how to come up with these kind of one-off acquisition ideas, but instead, how can you identify outside-the-box buyers for the companies you are trying to sell in a systematic and logical way?

To uncover these “not-so-usual” suspects, it is helpful to think like a strategic buyer.

Thinking Like a Strategic Buyer

A strategic buyer is looking for an acquisition target that will make a long-term impact on their business. Depending on their strategy, at any point in time, some companies may wish to enter new geographies, some may want to obtain particular technical capabilities, some may desire to be closer to their suppliers, known as backward integration, while others may wish to be closer to their customers, known as forward integration.

For many corporations with plentiful resources that need to be deployed profitably, the main strategic planning challenge is not a lack of opportunity. Instead the difficulty lies in establishing an efficient way to take inventory of all possible opportunities, sort them in an intelligible way, prioritize them objectively, and then allocate resources accordingly.

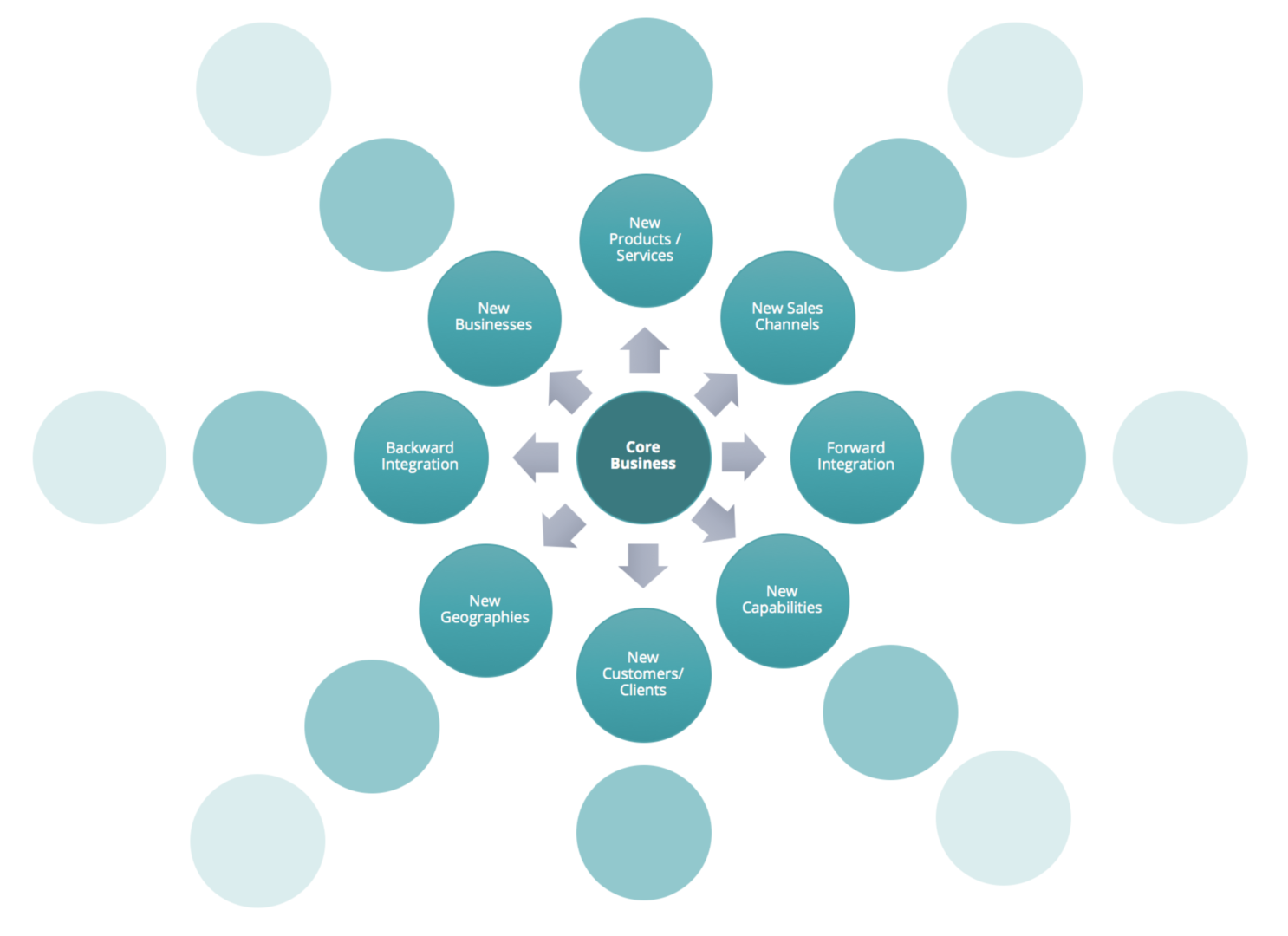

The Adjacency Map can help streamline the strategy development process by organizing, visualizing, and summarizing all opportunity sets by classifying them based on their proximity to a company’s core business today. Chris Zook and James Allen pioneered this approach in their landmark book Profit from the Core: A Return to Growth in Turbulent Times. Zook expanded upon this approach in Beyond the Core: Expand Your Market Without Abandoning Your Roots.

The Adjacency Map starts with the core business of a company as the central node of the map. Then, the map branches out in different directions, with each branch representing a different way to classify opportunities such as adding new capabilities or entering new geographies. In each direction, the closer each node is to the core, the more similar the opportunity is to today’s business. Think of it as establishing new incremental beachheads and then “island hopping” to the next objective.

To illustrate, take the Geography branch as an example. Assume you are US-based company with nation-wide presence, selling in the US alone. Expanding into Canada would be the nearest geographical node to today’s core business due to Canada’s proximity to the US, deep trade relations, legal institutions, and cultural similarities. In this example, expanding in Asia would be in an opportunity node further out from today’s core.

The branches of the Adjacency Map include:

#1. New Geographies – Expand physical footprint into new territories, starting with the closest one first, then expanding further after the presence in the first adjacent area is sufficiently consolidated and secure.

#2. New Verticals – Using similar core products/services that you excel at today, begin offering them in the most similar attractive vertical. For example, if you are a service provider for maintaining and refurbishing diesel engines for heavy duty equipment, you could consider beginning to service off-road diesel generators first, and later on, move onto servicing diesel marine engines. In other words, due to the similarities between large diesel engines, in essence, you are providing the same service in new verticals.

#3. New Products – Introduce new products to sell to your existing customers in your existing markets that nonetheless leverage your existing capabilities. For example, if you sell technical polyurethane foams for controlling engine vibrations to a Tier 1 Automotive supplier, you can begin selling a different grade of your polyurethane foams tailored for controlling road harshness or suspension-related vibrations. In this case, the new products use the same core know-how of polyurethane chemistry as the ones you make today. Similarly, the new products are sold to your current customers so that you can leverage the goodwill you have already built with them.

#4. New Sales Channels – Use different approaches to access more customers similar to the ones you already have. For example, if you make organic frozen meals targeting millennial customers and predominantly sell one-serving SKUs online, you could add family-sized multi-serving SKUs of the same product to sell to a married millennial through a club channel like Costco. Afterwards, you could consider expanding into the natural foods stores through strategic partnerships with distributors in the space. The key when adding new channels is to find more and new ways to access similar customers to increase sales, reach, and scale.

#5. New Capabilities – Adding a capability that complements today’s core can add know-how and value to the organization. For example, if you are a web development firm focused on difficult customer projects displayed on a browser, you could explore building a capability to create native iOS or Android apps to better display your content on mobile devices and differentiate your services from your competitors. You can then use the native mobile programming knowledge to jump into computer software programming eventually should you deem it an attractive market.

#6. New Business – Enter a new business that makes use of your current capabilities and exploits a favorable market positioning. For example, if you make a novel scientific instrument that requires a steep learning curve for lab technicians to use, you could consider providing consulting services to the audiences that would use your product. Thus, you are entering the consulting business, beyond your current product manufacturing business. The key distinction is that, unlike new products or new capabilities, adding a new business requires a changing of mindsets because, in general, service companies can be radically different organizations than product-focused companies.

#7. Forward Integration – Move one step closer to the final end-markets in your value chain.

#8. Backward Integration – Move one step closer to a raw material supplier in your value chain.

As you can see, the Adjacency Map is a great way to brainstorm ideas for where to grow next. From the perspective of a buyer, it is a powerful tool, since in any node of the Adjacency Map, there is a rich universe of potential acquisition targets that would not have come to mind when only considering the day-to-day competitors and/or usual suspects.

When considering the Adjacency Map as a strategic framework, the deals mentioned earlier in this account no longer seem as shocking. The method to the madness becomes much clearer. In the case of Microsoft, LinkedIn added a vast and highly complementary set of services for users of Office 365; for CVS, Aetna represented an adjacent new business; for Amazon and Walmart, Plug Power provided them with both backward integration as well as a new capability.

Leveraging the Adjacency Map to Find Buyers

Visualizing the Adjacency Map is helpful for companies looking to either acquire and/or divest. At Crossroads, we use the Adjacency Map to help both sell-side and buy-side clients find unique, qualified targets that they may have overlooked or may have never considered at all.

The adjacency map is a two-way street. Different companies in different adjacent nodes can both grow by moving into each other’s node. Just like a buyer can find targets by looking in its adjacent node, so can a seller find potential buyers.

What makes the Adjacency Map particularly powerful to a prospective seller is that it not only helps identify and qualify more strategic buyers, but also — and more importantly — it helps you craft the right investment thesis for buyers with different transaction rationales. For certain buyers, your company may be a capability play; for others it may be an opportunity to enter a new geography. Armed with these insights and intelligence, you can adjust your deal messaging to ensure that your company best resonates with the target’s key decision makers.

Key Takeaways

Creating a comprehensive Adjacency Map for your business can be a time-consuming and research-intensive process, but it is also aspirational. By mapping out your adjacencies you can better visualize your market environment, clarify your strategy, and prioritize your actions. This exercise can help you identify new growth opportunities for your business as well as reveal multiple paths to growth and optimal exit.

If you decide to compile an Adjacency Map for your company, the following tips can help you get started:

#1. Define your core business first — this will help anchor your map and allow you to clearly differentiate between the various its various branches;

#2. Do your homework — you may be intimately familiar with some branches of the Adjacency Map due to your day-to-day experience and less so with others. Where you are unfamiliar, conduct some basic research to familiarize yourself before proceeding and don’t give up in the exercise. The branches most unfamiliar to you can reveal the some of the most interesting opportunities;

#3. Don’t be afraid to think outside the box — the more ideas the better. Think about a group exercise with your senior team to ascertain their thinking; and

#4. Prioritize ideas only after you have taken full inventory of all possibilities – do not disqualify an idea too early.

Click here to learn more about the Crossroads Strategy process

Click here to learn about the Crossroads Sell-Side M&A process

Click here to learn about the Crossroads Buy-Side M&A process